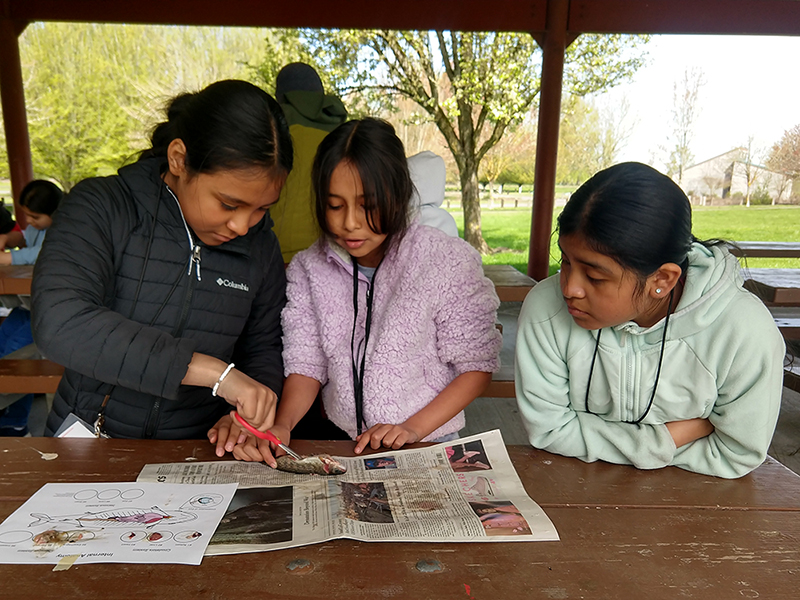

The students sat in pairs under a picnic shelter at Vancouver Lake Park, each set poised before a small trout laid out on a piece of newspaper. It was dissection day, but these students got to be outside at a local park instead of inside their classroom. They were full of questions:

Why do they have a line across their body? That is their lateral line and helps them sense and “hear” things in the water.

Where did the fish come from? From a local fish farmer.

What happens to the fish after we’re done? They are composted to fertilize plants.

The students counted up each salmon’s fins (eight), located and identified organs from its circulatory and digestive systems, and examined how, if they look through its eye lens the world looks upside down.

This is the third field trip these students—4th graders from Sarah J. Anderson Elementary School in Vancouver—have had with Estuary Partnership educators. Thanks to an Outdoor Learning Grant from the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office, these students and more than 400 others like them at five other Clark and Cowlitz County schools have had the opportunity for hands-on learning about nature and their watershed throughout the school year.

Their series of lessons started out in their classroom and in their schoolyards. In the fall they learned about native plants and got to explore on our Walkable Watershed Map, discovering where they live in connection to the whole Columbia River watershed. Then they got to use those lessons at Burnt Bridge Creek, where they planted native trees and shrubs to improve a part of their local watershed.

This spring, they learned about bird beak adaptations and spent time nature journaling. On another day, they examined schoolyard quadrants to identify insects and other foods for native birds, and on yet another they sought out detritivores that help to break things back down into the soil. Seeing what life exists in the area right around their school is a new experience, and many students were surprised at all the different species they found.

Later at Vancouver Lake, the kids took a leisurely nature hike around the park’s trail system. The entire class was very excited to hear a rhythmic tapping in the woods above them. Educator Sam asked the students if they knew more about what made the sound. This brought them back to their bird beak lesson earlier in the spring, and they excitedly announced that it must be a woodpecker looking for insects to eat. These students, from a bilingual immersion classroom, tried to recall what a woodpecker is called in Spanish. One student announced it was “el pájaro loco” – crazy bird – for slamming its head into the trees. Later they would figure out the real name is el pájaro carpintero – the carpenter bird.

A few weeks later, the students were outside in the field again to explore Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge. This was their final field trip in the program—and of the whole school year. They were excited to visit a park that was so close to home, but where most of them had never been before. They started with a nature hike on the Oaks to Wetlands Trail, exploring the Oregon white oak habitat and looking for signs of wildlife. Stopping briefly by the Cathlapotle Plankhouse, they learned that there used to be many of these large, communal houses along this stretch of the river, and how the Chinook Indian Tribe continues to use the plankhouse for ceremonies and gatherings today. As they moved onward, they spotted lots of garter snakes and kept a keen eye out for birds. They spotted bones by the trail and speculated that they might be from a coyote. They were also intrigued by the oak galls and took one to dissect later.

Their final learning activity together with our Educators was the Ridgefield auto-tour route, a popular birding route at the refuge. Students were prepared with binoculars and bird guides to identify as many birds as they could. As their bus slowly crept along the 4-mile route, shouts periodically arose as students spotted new birds and other wildlife.

“An egret!”

“I see ducks! I think they’re mallards.”

“I see a nest!”

The students were also delighted to see deer—lots of Columbian white-tailed deer were out foraging that day. The students kept a list, also spotting robins, song sparrows, redwing blackbirds, blue heron, a cinnamon teal, a sandhill crane, a swan, a beaver lodge, and a well-camouflaged American bittern. Even better is that some of the students talked about coming back to the refuge with their families.

Many thanks to the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office's Outdoor Learning Grant for support to ensure eager students like these have a healthy dose of outdoor learning throughout the school year.