Changes in climate are shifting our approach to conservation.

In 2016, we adopted voluntary targets for recovery of native habitat to meet an overall goal of historical habitat diversity and protection of biodiversity. These targets are aggressive, but they address recovering historical habitat. Yet we know now that climate change is fundamentally altering ecosystem processes and species ranges. We know we must adapt our methods.

We are looking at the changes we need to make in our conservation and restoration programs to protect biodiversity as climate change disrupts critical relationships that species have adapted to over millennia. We know that plants and animals are shifting or expanding their ranges, often poleward and to higher elevations; plants are leafing out and blooming earlier, and wildlife are breeding and migrating earlier; and changes in hydrological conditions are affecting life-cycle events, such as fish migration in snowmelt-driven rivers.

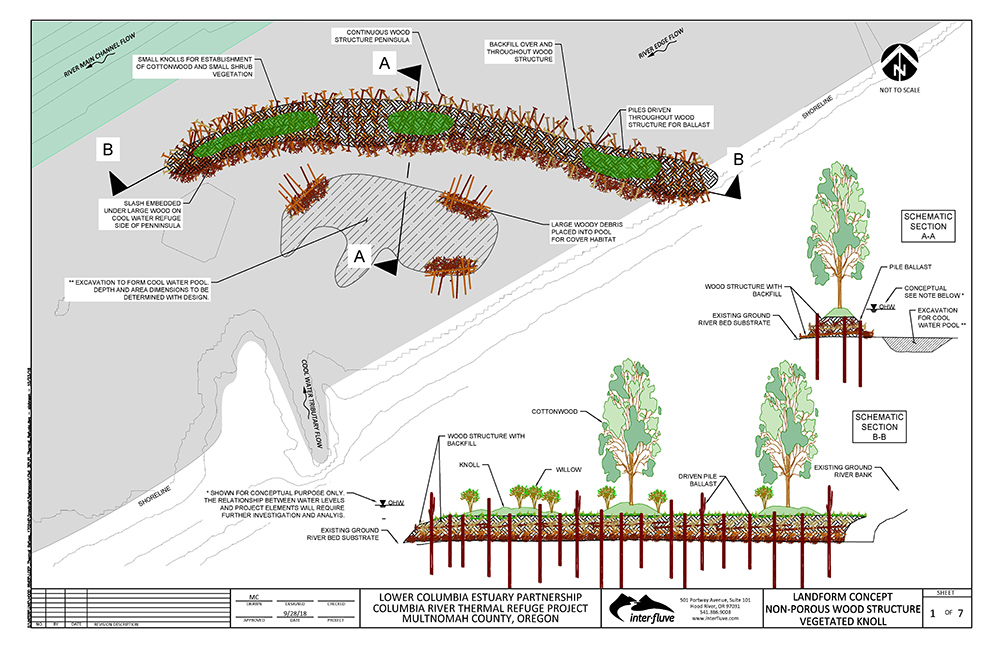

To be “climate-smart” in our conservation program, we evaluated several potential conservation approaches to adapt our habitat coverage targets, including protecting climate refuges for salmon and steelhead. In 2015-16, we assessed confluence temperatures for tributaries from lower Columbia River Gorge to Longview, to determine if they provide suitable thermal refuge. We identified a 57-mile gap between the Lewis River and Eagle Creek where suitable thermal refuge for migrating salmon does not exist. We then evaluated new techniques to enhance and/or protect them for cold water species over the near term. We now are designing a pilot project for construction in 2021, which will use physical barriers to catch cold tributary water, amplifying its plume so it will be large enough for salmon to locate and use (see diagram below). As Columbia River summertime temperatures continue to increase, the importance of such cold water for migrating salmonids will be even more important.

We also are assessing how sea level rise will affect our ability to meet our habitat coverage targets. As ocean sea level rises, water levels in the river and estuary will rise as well, affecting the location of tidal wetlands. Wetland habitats provide a wide range of benefits to humans and other species—protection from storm surges and flooding, habitat and food for hundreds of species, filtration of pollutants and improved water quality—so it is important to quantify the potential impacts that rising seas will have on present day wetlands. Preliminary studies estimate the potential loss of up to 65% of estuarine and floodplain habitats from sea level rise for the region from Puget Sound to Tillamook Bay, but those studies did not specifically target the lower river. In 2018, we developed a model to quantify and map haw various sea level rise scenarios could cause tidal wetland migration throughout the lower Columbia River. This analysis mapped areas where wetlands may be lost, migrate upslope, or remain intact. Results suggest that sea level rise may overtop portions of the widespread network of levees in the lower Columbia floodplain. This analysis provides an opportunity for adaptations that anticipate, rather than react to, climate shifts. Our critical next step is to develop design standards or best practices for floodplain protection and fish passage projects that integrate the increased water levels and flooding predicted from sea level rise and more intense storms.