Have you visited one of Southwest Washington’s wildest rivers? If you’re fishing in search of the biggest catch, a birder looking to lengthen your list, a hiker chasing waterfalls, or a boater seeking a thrill, then you have probably spent time on the East Fork Lewis River – a river often called the gem of Clark County.

In addition to what this river provides for people, the East Fork Lewis River is essential to the recovery of wild salmon and steelhead. It is an undammed, free-flowing river that supports five native salmonid species: summer and winter steelhead and coho, chum, and Chinook salmon. The river was designated a wild steelhead gene bank in 2014, meaning that no hatchery fish are released into the river. Additionally, the river supports populations of Pacific lamprey, freshwater mussels, numerous species of waterfowl, and many other native aquatic and terrestrial species.

Despite its accolades, the East Fork Lewis River has serious problems. Most significantly, development and legacy gravel mining along the lower portion of the river has eliminated essential floodplain habitat and transformed stretches of the river that were once complex, multi-threaded river systems with extensive floodplain habitat into a single channel bound by levees and other forms of hard infrastructure.

Why we're restoring the East Fork Lewis River

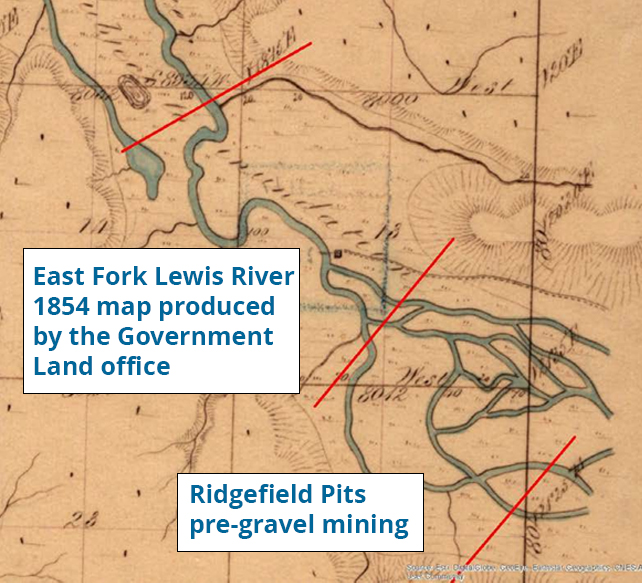

Development and legacy gravel mining along the lower portion of East Fork Lewis River eliminated a significant amount of the river’s floodplain habitat and drastically altered its path. Historic maps from the 1850s show the East Fork Lewis River as a complex, multi-channel river with vast floodplain habitat, wetlands, alcoves, and side channels. After decades of gravel mining, levee construction and channel manipulation, this stretch of river now flows in a single channel.

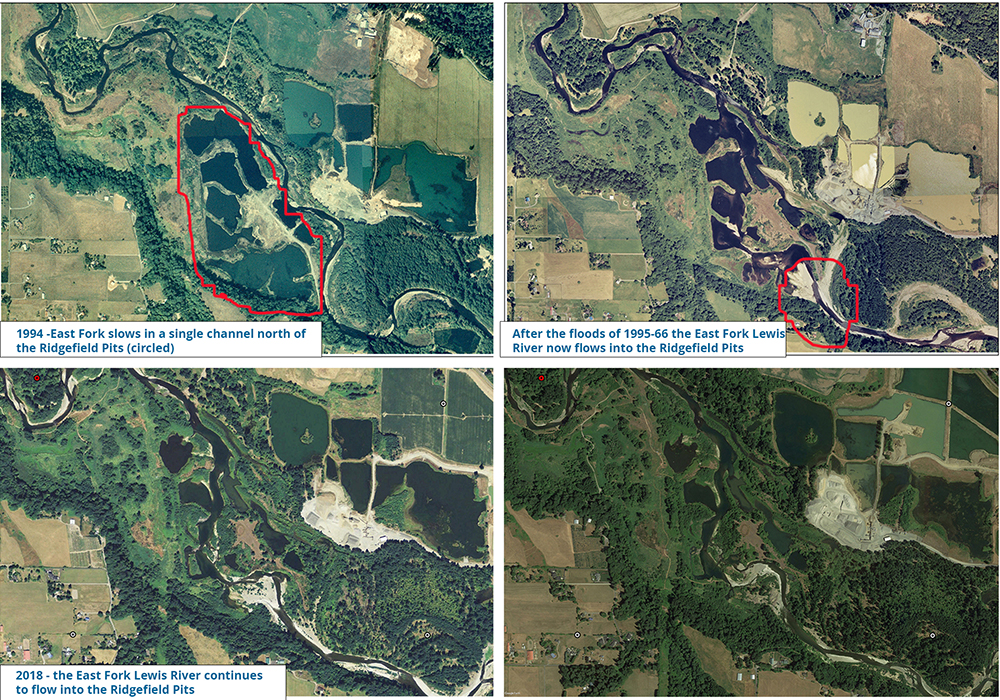

During the 500-year flood event in 1995-96, the single channel East Fork Lewis River caused devastating impacts when it broke through the levee on the river’s south bank and into nine abandoned gravel pits known as the Ridgefield Pits. Formerly active floodplain habitat, the Ridgefield Pits were mined for gravel in the early part of the 20th century.

To this day, the East Fork Lewis River continues to flow through the gravel mining pits. This stretch of river is now disconnected from much of its floodplain and the historically complex, multi-threaded channels have been replaced with a simplified, single channel. The result is an area that is overrun with non-native plants and has an over-abundance of fish that prey on juvenile salmon. Furthermore, this stretch of the river often creates a temperature barrier for migrating salmon and steelhead (when water temperatures become too hot, salmon and steelhead may delay their upriver travel to spawn – this delay can severely lower spawning rates, thus impacting future generations of salmon and steelhead).

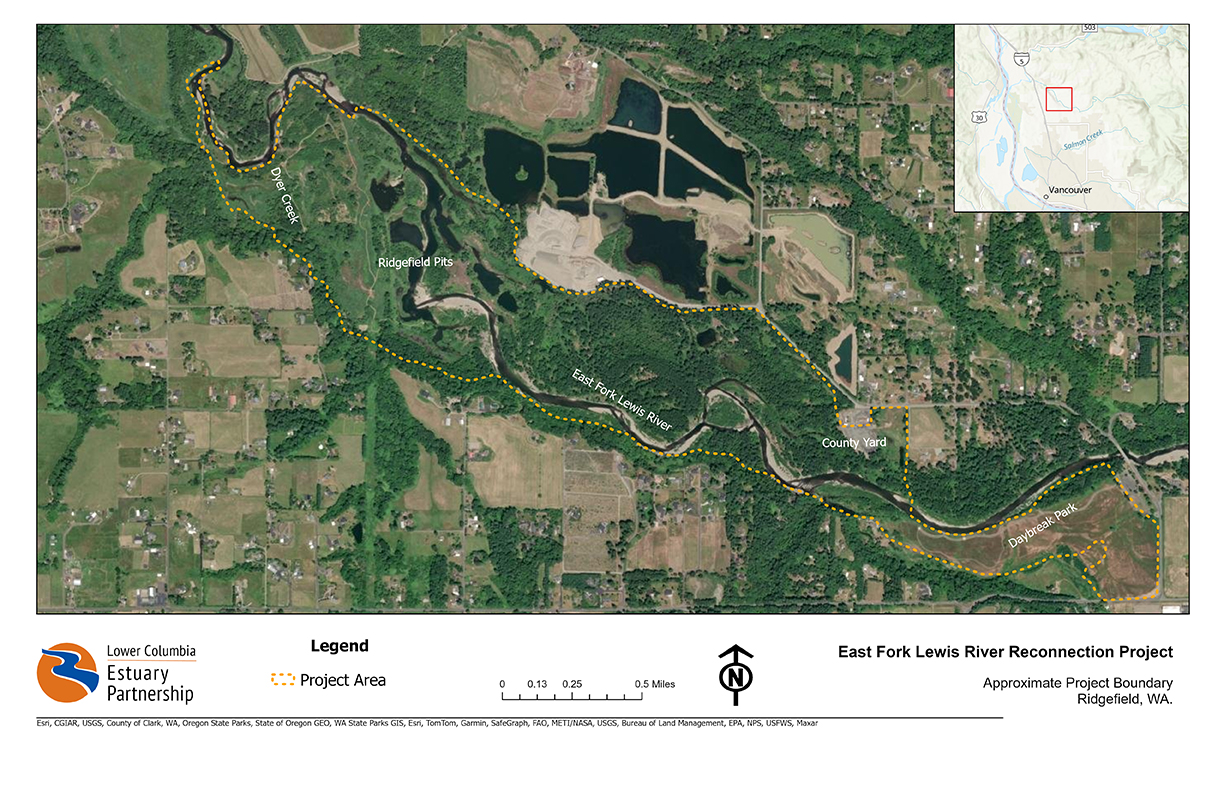

To address these serious issues, the Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership, Clark County, and many other partners are implementing the East Fork Lewis Floodplain Reconnection Project. Spanning three river miles, the East Fork Lewis River Reconnection Project is the largest restoration project ever on the East Fork Lewis River.

Benefits of restoring the East Fork Lewis River

Floodplain restoration: Floodplains are dynamic areas of land adjacent to river channels that regularly flood when waters rise during storms or when the snow melts. The slow moving, nutrient rich conditions created by floodplains provide essential habitat for juvenile salmon and steelhead. Numerous studies demonstrate that juvenile salmon reared in floodplains grow larger and have better survival odds than juvenile salmon raised in mainstem river conditions where waters move more swiftly and food is harder to come by. Click here to read a study conducted by the University of California Davis.

Beyond benefits for salmon and steelhead, floodplains lower the intensity of flood events and harmful erosion by giving the river more room to expand and adjust naturally. They also allow flood waters to soak into the ground, recharging groundwater reserves. Some of this cold groundwater is released back into the river during summer months when water levels in the river are low, thus helping to alleviate warm water conditions that are stressful to salmon and steelhead.

Multi-channel restoration: Prior to gravel mining and development, the stretch of the East Fork Lewis River slated for restoration was a complex, multi-threaded river channel. It contained floodplains, wetlands, alcoves, and side channels. This ecosystem provides habitat for salmon to spawn, and a diversity of native flora and fauna to thrive.

A study conducted downstream of the project area on the East Fork Lewis River at the LaCenter Bottoms demonstrated that floodplain wetland habitat on the river were some of the most productive habitat for juvenile coho and Chinook salmon in the region. The study of this highly productive area helped to inform the East Fork Lewis River Reconnection Project’s design. Click here to read the study.

So much of this complex, multi-threaded habitat has been lost in river systems throughout the region. Increasingly, watershed scientists are advocating for the restoration of this type of habitat as a way to reconnect floodplains, recover food webs, raise the water table, and decrease flood and erosion risk. This approach to restoration and flood management is also a response to decades of failed (and expensive) attempts to control a rivers’ path using “hard” infrastructure like levees

Additional benefits for the people

The East Fork Lewis River Reconnection Project is a $20 million restoration project. Funding for this project was awarded by separate state and federal agencies through highly competitive processes. Without such a robust, compelling, and community-supported project, these grants would have gone elsewhere in the state or nation.

Not only will the East Fork Lewis River Reconnection Project be a boon for the river and its fish, wildlife, and human inhabitants, the project is expected to generate more than 332 new or sustained jobs while adding roughly $43.7-49.7 million in total economic activity. Roughly 80% of the economic activity generated by this project is expected to stay in Clark County. The Estuary Partnership’s most recent large-scale habitat restoration project, the Steigerwald Reconnection Project, demonstrated the economic benefits of habitat restoration and flood-risk reduction projects in Clark County.

Click here to read an editorial in the Vancouver Business Journal about the economic benefits of the Steigerwald Reconnection Project written by representatives of the Estuary Partnership, Rotschy, Inc., and the Port of Camas-Washougal.

Local workers are not the only ones expected to benefit from the East Fork Lewis River Reconnection Project. The Estuary Partnership will pair community and student engagement programs with the project – turning a habitat restoration project into a learning laboratory benefiting local schools and residents. Another benefit associated with the East Fork Lewis River Reconnection Project is that it completes a key link in Clark County’s greenway trail extending along the river from Daybreak Regional Park to Paradise State Park. Click here to learn about Clark County’s Legacy Lands program.

Developing the East Fork Lewis River Reconnection Project

Correcting the historic loss of floodplain habitat, including the river’s flow through the Ridgefield Pits is a massive challenge. And we’re ready to tackle it. Planning for the restoration of the most-impacted stretch of river – three river miles between Daybreak Regional Park and the Ridgefield Pits – has been underway for nearly a decade.

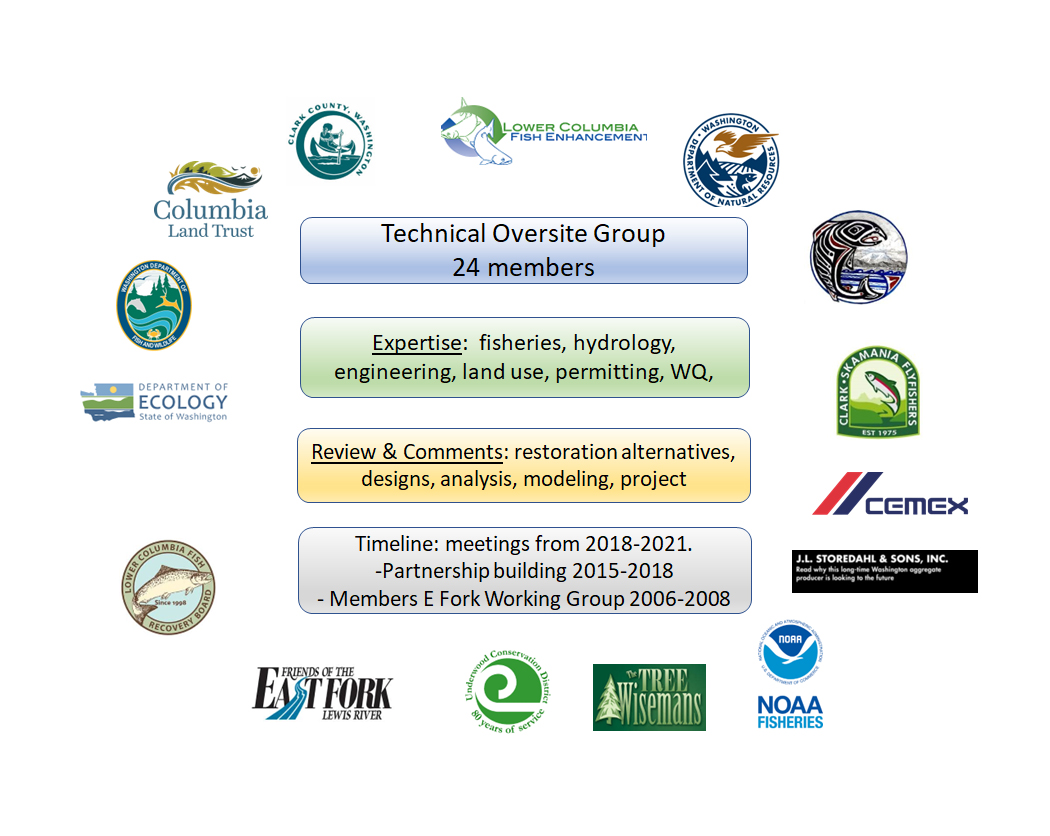

With the support of a large Technical Advisory Group, the Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership worked with landowners, state and local governments, environmental nonprofits, community organizations, and a tribe to develop a plan to reconnect the river to its floodplain and recreate the East Fork Lewis River that existed prior to gravel mining and other development. Resetting this highly disturbed stretch of river to its natural state not only benefits salmon, steelhead, and lamprey, it makes the homes and businesses adjacent to the river more resilient to flooding and erosion and boosts the local economy.

The East Fork Lewis River Floodplain Reconnection Project is currently undergoing an extensive permitting process. This process builds upon years of necessary scrutiny and review and helps to ensure that this important reach of the East Fork Lewis River is restored to a condition that will once again resemble its natural condition. The project is expected to break ground in 2025. Construction will take two to three years to complete, with revegetation efforts continuing for several years after that.

-

Lower East Fork Floodplain Reclamation in the news

Grant awarded to East Fork Lewis River Restoration Project. The Columbian. September 30, 2022

More than $7M awarded for East Fork Lewis River Restoration. The Reflector. October 10, 2022

Advocates push legislature to fund East Fork Lewis River work. The Columbian. March 30, 2023

WA could get million in federal salmon recovery dollars. The Seattle Times. April 21, 2023

Federal, state grants set for East Fork Lewis rehab project. The Reflector. May 1,2023

Restoration group gets $5.4M for Lewis River floodplain project. The Daily News. September 9, 2023

-

Support for the Lower East Fork Lewis Floodplain Reclamation Project

“This ambitious project will restore a significant reach of the watershed and benefit Endangered Species Act listed salmon and steelhead, restore watershed processes impacted by past and current land uses, and protect important public and private infrastructure. This project represents one of the most significant opportunities for large-scale floodplain restoration in the watershed.” Ian Sinks, Stewardship Director, Columbia Land Trust

“This project represents the single greatest opportunity to conduct broad scale floodplain reconnection, restoring function to a three-mile long, multi-species reach of the East Fork Lewis River. Increasing habitat capacity and diversity in this high priority stream corridor provides a strong certainty of success for supporting viability improvements for five Endangered Species Act-listed salmonid runs." Steve Manlow, Executive Director, Lower Columbia Fish Recovery Board

"For Rotschy Inc., the project [Steigerwald Reconnection Project] not only was a perfect fit, but an exciting business opportunity. Massive earthworks projects fit easily in our wheelhouse, but the opportunity to construct 1.6 miles of setback levees was an exciting challenge and a strategic addition to our company’s portfolio. As a bonus, the refuge is located a short distance from our main offices; as a family business, projects that allow our employees to return home to their families in the evening rather than check into a hotel are very important to us." Darin Kysar, Project Manager, Rotschy Inc. Rotschy Inc was the prime contractor for the Steigerwald Reconnection Project, a previous restoration project led by the Lower Columbia Estuary Project and funded by Floodplains by Design; the Estuary Partnership commits to hiring local in the construction of the Lower East Fork Lewis Floodplain Reclamation Project.

“The East Fork Lewis River is a gem. It flows undammed, off the flanks of the Cascade mountains to the lower Columbia River, providing critical habitat to Endangered Salmon and Steelhead. The East Fork Restoration Project seeks to restore and reconnect a highly impacted reach of the lower river which, if left untreated, could take decades to recover from floodplain mining. WDFW fully supports this project and looks forward to its timely completion.” Alex Uber, PE, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

“DNR is proud to support the restoration work that the Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership has conducted on the East Fork of the Lewis River. Focusing on floodplain reconnection helps reduce the impacts of flooding on local communities and contributes to ecosystem health and recovery of our endangered salmonid species.” Renelle Smith, Assistant Division Manager, Aquatic Resource Division, Washington Department of Natural Resources

-

Type

Habitat